Japan is well known for its safety, order, and high quality of life, a perfect display of omote (on the surface) and ura (under the covers). Hidden away with many other dirty little secrets, there exists a dark and hidden underbelly of labor that remains largely in the shadows—yami baito, or dark part-time jobs. A baito is short for arubaito which is a Japanese loan word from German, arbeit, meaning part-time work. Yami simply means dark. These jobs, a far cry from the orderly and efficient workforce most associate with Japan, often involve illegal activities, dangerous conditions, or severe exploitation, attracting vulnerable people in need of quick cash or simply unaware of the risks involved.

Yami baito is when people are hired—often through anonymous postings on social media or shady job listing websites—to engage in work that may be illegal, dangerous, or unethical. These jobs can include anything from running scams, dealing drugs, and participating in theft, to more mundane tasks like factory work in unsafe conditions or underpaid cleaning work. In recent times, it also means home invasions that have more often than not led to the murders of elderly people.

People enter these jobs out of desperation, drawn by the promise of fast money with no formal qualifications or experience required. The appeal is particularly strong among Japan’s youth, students, and even foreign workers, many of whom may be financially struggling or unable to find stable employment.

What’s even more intriguing is that some of these yami baito were orchestrated from a jail in the Philippines, where the masterminds managed to recruit accomplices in Japan to carry out the robberies. The ringleader went by the nickname "Luffy" after a popular anime character and Japanese authorities had been hunting down the gang since the wave of crimes first began in the summer of 2021, one which resulted in the murder of a 90-year-old woman in Tokyo in early 2023.

One of the driving forces behind the rise of yami baito is economic pressure. Despite Japan’s robust economy as the world’s number 4 economy, not everyone shares in its prosperity. This is one of the premises of my documentary “The Ones Left Behind: The Plight of Single Mothers in Japan.”

Japan’s aging population and stagnant wages have left young people with fewer opportunities for full-time employment. Wages have not changed since I first started working full-time in Japan in 2001. Coca Cola prices at the vending machines are still the same as when I first step foot in Japan a year earlier, in November of 2000.

Full-time employment is known as regular work. I break down regular and non-regular work in Japan in my substack post “Single Mothers in Japan and Australia” and why single mothers in particular fall victim to the non-regular employment trap.

Foreign workers, many of whom come on limited visas, are often even more vulnerable to economic hardships in Japan as they can face barriers to traditional job markets due to language, legal status, or unfamiliarity with labor laws.

The digitisation of recruitment has also made it easier for shady employers to hide in the shadows. On social media apps like X (Twitter), LINE, Signal and Telegram, yami baito offers can be circulated quickly and anonymously, promising high pay for vague work descriptions. The initial allure of these jobs is undeniable—no prior experience required, flexible hours, and little oversight—but the true nature of the work is often revealed too late, when workers find themselves entrenched in criminal or highly exploitative activities. I know this first hand because one my most commonly searched X keywords in Japanese is “single mother” to see if my documentary is being talked about. More often than not, photos and information like this appear. Here is a screenshot I took just now:

Social media platforms like these are the perfect platforms for recruiting yami baito workers. The anonymity afforded by encrypted messaging apps allows recruiters to cast a wide net, targeting young people and vulnerable populations who may be struggling financially. Posts advertising “high pay for easy work” catch the eye but details of the job are always vague until it’s too late.

Once hired, workers are instructed to maintain secrecy, often paid in cash to avoid a paper trail. These jobs often promise immediate cash, drawing in individuals who are not in a position to question the source of income. The use of temporary communication apps makes it easier for recruiters to disappear if things go wrong.

The work itself can be physically dangerous and legally precarious. Many yami baito involve running furikomi sagi, or bank transfer scams, where individuals pretend to be legitimate organisations or the police, and trick people—often the elderly—into sending money. In other cases, workers might be involved in money laundering schemes, or even act as middlemen in the drug trade. What you are seeing is the evolution of the modern day gangster.

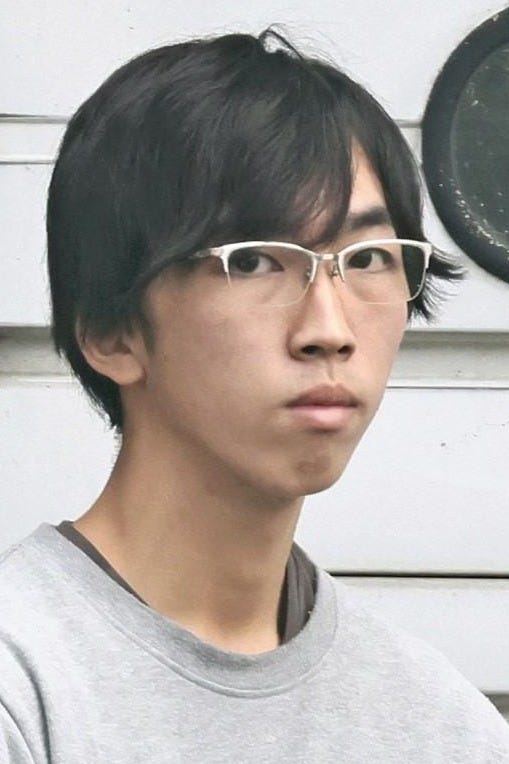

In addition to the obvious risks of engaging in illegal activity, workers face the constant threat of violence from organised crime groups like the yakuza or other predatory employers. There are numerous stories of individuals who have been beaten, threatened, or otherwise harmed after trying to leave these jobs or refuse certain tasks. Just a few days ago, a 22 year old boy broke into the house of a 75 year old man and beat him dead, stealing only 200,000 yen (less than $2000) before fleeing. When captured, he told the police that the people who employed him threatened to kill his entire family if he didn’t go through with the robbery. Like everyone else who signs up for these supposedly quick and easy money jobs, he had sent a copy of his license to the employers. From The Yomiuri Shimbun:

Takarada was quoted by police as saying he was in arrears for several hundred thousand yen in taxes and was looking on social media for a part-time job that would allow him to earn money in a short period of time, and he applied for a job after finding a post that seemed like a legitimate job. However, he said: “I realized that I was going to be involved in a crime along the way, but I couldn’t refuse because I thought my family might be harmed,” according to the police.

Japan has seen an incredible rise in violent home break-ins and murders linked to yami baito with the intruders targeting homes in both urban and rural areas. The increase in violent crime has prompted concern among citizens and led authorities to heighten security measures while intensifying their investigations. Despite Japan's low overall crime rate, these shocking incidents highlight vulnerabilities and a growing fear among residents.

Law enforcement agencies are becoming increasingly aware of yami baito and efforts are being made to crack down on illegal recruitment. Social media companies are also under pressure to monitor and remove posts promoting dark part-time jobs. However, the decentralised and anonymous nature of these jobs make it difficult to stamp out.

Yami baito is a disturbing yet growing trend in Japan’s part-time job market, highlighting the darker side of Japan. It offers a quick solution to financial hardship but often ends in the ones at the bottom taking the fall and the ones at the top escaping into the night. The issue requires a concerted effort from both the government and society at large to ensure that vulnerable individuals are protected, and that Japan’s labor market remains a place of legitimate opportunity, rather than exploitation.

About Me:

For those who don’t know me, I’m Rionne McAvoy, a documentary filmmaker, pro wrestler, and martial artist. I’ve been living in Japan for over 22 years, and my passion is telling stories that matter—stories that inspire change, that make people think, and, most importantly, that give a voice to those who need it most.

About the Film:

The Ones Left Behind: The Plight of Single Mothers in Japan is a documentary that reveals the hidden poverty facing single mothers in Japan, highlighting their struggles to provide for their children in a society that often leaves them behind. The film has already won several awards and is now gaining international attention.

Thanks Rionne, insightful story that helps showing a different side of Japan.