While this substack may take you minutes to read, writing it took me months. I had to get it right, it’s an issue very close to my heart. This piece came together after a couple of incidents that took place in Australia when I was home recently, where I saw the full force of the domestic violence epidemic that is destroying Australia and the global challenges of being a single mother. It took every last bit of knowledge I have attained over the past 3 years from on the ground interviews and off camera conversations in both Japan and Australia to put it together, combined with hours of research on the topic. I have provided links to the research throughout. What I can tell you from all this is simply one thing; mothers, and in particular single mothers, are warriors. A mother’s pride is something I will never be able to comprehend, but it’s always on display in all walks of life.

Before I go any further, I need to plug the documentary. If you’re in Tokyo in November, please come down and watch the film and support independent filmmaking. I’ll be there every morning. More info here:

Single motherhood is a global challenge, but the experiences of single mothers vary widely depending on the country's social support systems, cultural expectations, and government policies. I have now spent more time in my life in Japan than I have in Australia, and while both countries are developed nations, they offer different landscapes for single mothers. I know because it’s a topic that is very close to home for me in both countries. On the surface, Australia provides better welfare and more progressive policies than Japan, but the truth is that it still lags behind so many other countries worldwide. Both Australia and Japan have room for improvement, particularly in addressing domestic violence and financial insecurity, issues that disproportionately affect single mothers.

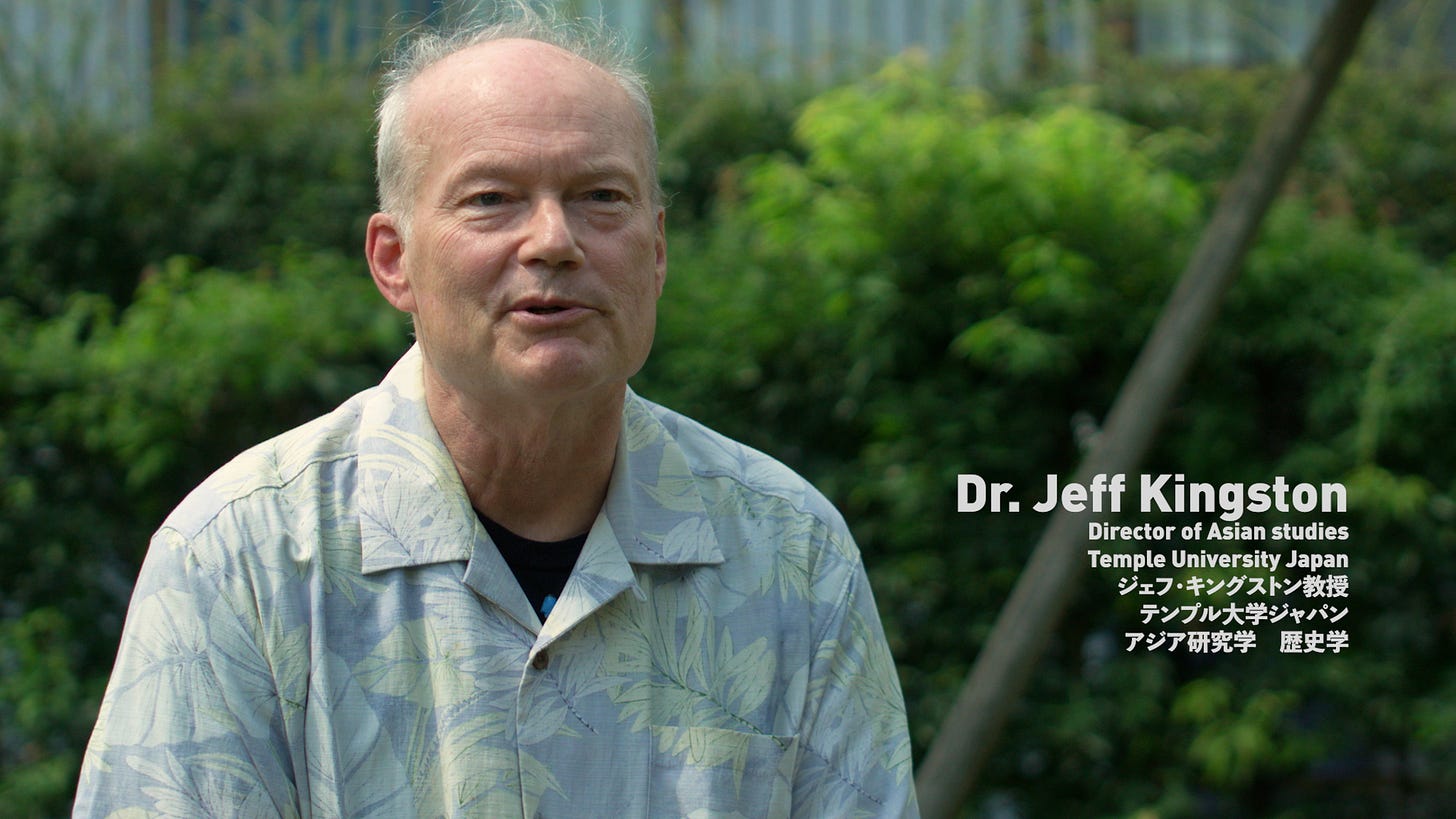

Dr. Jeff Kingston told me in the summer of 2021 that Japan has one of the highest rates of child poverty in the developed world, with single-mother households being particularly vulnerable. I did not believe him, only because he used the word “poverty.” Could it really be? Poverty in Japan? When I heard this from Jeff I had been living in Japan for 19 years and could not see it. In my mind, it did not exist. Yet the truth is that 1 in 7 children here in Japan are in poverty. The OECD defines poverty as households with income below 50% of the median household income.

So how can Japan be so poor, yet so few people actually know about it? I use this term “hidden poverty” because the reality is hidden under the proverbial tatami mat by the Japanese government. Why? Because Japan is a country of outside and inside faces. There are so many ways to describe this concept in Japanese. Omote/Ura or Uchi/Soto, and of course honne/tatemae are concepts we learn when we first arrive in Japan.

Japan has an image it wants to show to the rest of the world. Why do you think the Japanese government gave 30 billion US dollars in aid to Africa as recently as 2022? This is 30 billion for 3 years, coming in at a cool 10 billion USD per year. Could the Japanese government only give Africa 20 billion dollars instead? What would you do with that extra 10 billion?

Is Australia any better at dealing with child poverty? In my motherland, 1 in 6 Australian children are in poverty, a figure that highlights significant social welfare challenges. While Australia has somewhat stronger support systems for single mothers compared to Japan, both face severe shortcomings when it comes to addressing the needs of vulnerable children and families.

Japan and Australia only need to look at countries like Sweden, Norway, and Denmark who provide stronger safety nets, including comprehensive child care, housing assistance, and parental leave, which alleviates much of the financial burden single parents face.

Back here in Japan, despite the cultural emphasis on family unity, single mothers often face deep social stigma that does not seem to exist in the countries mentioned above. The reason? Akihiko Kato, a professor from Meiji University, told me in the documentary that Japanese society heavily favors traditional two-parent households, leaving single mothers on the margins. He is Japan’s foremost expert on the nuclear family model.

Government support for single-parent families in Japan is minimal. Single mothers are typically left to navigate the high costs of living and childcare on their own. The child-rearing allowance (Jido Fuyo Teate), designed to assist single parents, is often insufficient, and many women are forced into low-paying jobs with little security. Dr. Greg Story informs us in the documentary that around half of Japan’s single-parent households live in poverty, a shocking statistic in such an advanced economy. What’s even more shocking? 86% of Japan’s single-parent households work full time work hours.

The lack of affordable daycare and flexible working arrangements only adds to the struggle. Many single mothers here in Japan must work multiple part-time jobs, often in non-regular jobs, to make ends meet. I truly believe that non-regular work is one of the root causes of poverty amongst single mothers in Japan, making it nearly impossible for these women to break free from their financial struggles.

What is a non-regular job?

After I interviewed Dr. Kingston, I had to go back and look this up. I didn’t quite understand the differences. It’s actually quite a simple concept.

In Japan, a regular job is a regular job. You have your benefits and guarantees. In Australia, these benefits are some of the best in the developed world. A non-regular job is the opposite. It is any form of employment that is not considered full-time, permanent, or standard. This includes part-time workers, temporary staff, contract workers, dispatch workers, and others who do not have the same employment benefits, stability, or job security as seishain, the regular employees. Non-regular workers face lower wages, fewer benefits (such as health insurance, pension contributions, and paid leave) and have far less job security. Their contracts are often short-term and they have limited career advancement opportunities compared to regular employees.

I found all this out when our unnamed single mother (I had to blur her face out in the film as she was afraid of what her ex husband would do if he saw the film) told me that she had twice begged her employer to make her a seishain, a regular employee, but they refused. The reason? She was a single mother.

While Australia performs better than Japan in terms of financial assistance, several countries stand out as having exemplary social welfare systems for single mothers. It’s no surprise that these are all Scandinavian countries:

Sweden is often hailed as a model for gender equality and social welfare and indeed was the country I used in the film to show how a nation should treat their single mothers. Sweden provides single mothers with comprehensive support, including generous parental leave, heavily subsidized childcare, and great financial benefits.

Similar to Sweden, Norway has a strong welfare state that supports single parents with financial aid, free healthcare, and affordable daycare. For these reasons, I was desperate to have the Norwegian Ambassador to Japan Kristin Iglum attend our recent Shibuya Human Trust Cinema screening. She obliged and told the audience what Norway was doing in terms of flexible working hours and paid parental leave, creating a more balanced work-life situation.

Another Scandinavian nation, Denmark, has a social safety net that single mothers receive high-quality childcare services, paid leave, and substantial financial assistance. The Danish government’s commitment to welfare means that single mothers are rarely left without a support system, drastically reducing child poverty rates.

Anytime I go home for a holiday to Australia, the topic of my film The Ones Left Behind: The Plight of Single Mothers in Japan always comes up. I know quite a lot of single mothers in Australia (compared to zero in Japan when I started shooting the documentary). These ladies all told me essentially the same thing - that Australia’s social welfare is very far from ideal. On paper things look great - single mothers in Australia have access to the Parenting Payment, a financial benefit that provides some relief, along with the Family Tax Benefit, which helps with the cost of raising children. In addition, Australia offers subsidized childcare and various other welfare measures aimed at supporting low-income families. The reality is that in 2006, and again in 2012, Australia made significant cuts to single-parent payments, forcing many mothers to find work before they were financially or emotionally ready.

In Japan in 2010, The Democratic Party of Japan increased welfare spending, including support for single-parent families but this was changed in 2012 when the Liberal Democratic Party (the party established and bankrolled by the CIA in 1955) returned to power. Single mothers were the victims of these new budget cuts.

While the social welfare system in Australia is generally better than Japan's, one critical area where my motherland falls short is domestic violence.

When I was back in Australia this past August, I learned about this from the women in the trenches. Through conversations with the ladies at Fierce Females, a registered charity and not-for-profit organisation that offers women's self-empowerment and defence programs on the Gold Coast, I found out about the domestic violence epidemic that is gripping Australia. The situation is so dire that Australia is teetering on the brink of social meltdown.

The Domestic Violence Epidemic in Australia

Domestic violence is a persistent and deadly issue in Australia, with women, especially single mothers, affected the most. In 2022, it was reported that on average, one woman is killed by a current or former partner every 9 days in Australia. The Australian Institute of Criminology's Homicide in Australia report shows 49 per cent of female victims of homicide were killed by a former or current intimate partner in the 2022-23 financial year. Single mothers who are also victims of domestic violence face the dual hardships of protecting themselves and their children while trying to battle financial and legal hurdles.

And how does this compare to Japan? Japan’s statistics are often outdated and not clear, one of the biggest challenges I faced whilst making the film. Domestic violence in Japan is a significant issue, as Fumi Hino tells me in the documentary. She was beaten pillar to post by her ex-husband, but only from the neck down. Again, outside face and inside face.

Also in Japan, domestic violence is often underreported due to social stigma and traditional cultural norms. According to the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare and the National Police Agency, the number of reported cases of domestic violence has been steadily rising over the years. I included a news clip of this in the documentary, but officially the Japanese police received 84,496 consultation requests regarding domestic violence in 2022, a record high for the 19th consecutive year.

The Australian government has introduced several initiatives to combat domestic violence, including hotlines, shelters, and financial aid for victims. For instance, the Escaping Violence Payment offers up to $5,000 in financial support to help victims leave abusive situations. Additionally, the Safe Places Emergency Accommodation Program funds emergency housing projects to provide secure places for women and children in crisis. Other programs include trauma-informed counseling services and financial assistance for improving home security, allowing women to stay in their own homes where safe and appropriate. But the reality is, it is not enough. The Queensland police have only recently just started taking domestic violence seriously after a damning report showed how terrible their responses were to it, as the ABC says “delivered a reckoning for the organisation”.

In contrast, countries like Finland have implemented programs such as emergency housing, financial aid, and legal protection for victims of domestic violence. Finland’s approach not only ensures the safety of women and children but also provides them with the resources to rebuild their lives, offering a potential model for Australia to follow.

We need to learn from each other!

I’ve said this all along. No system is perfect. While Australia offers a better welfare system than Japan in many respects, it’s clear that both countries have significant room for improvement. Japan needs to address the financial struggles and social stigma that single mothers face, while Australia must confront its domestic violence crisis and provide more long-term support for single parents.

Looking at countries like Sweden, Norway, and Finland, it's evident that comprehensive social welfare systems that include subsidized childcare, financial support, and robust protection from domestic violence make a world of difference for single mothers. Australia and Japan could learn from these countries by adopting more progressive policies to support one of society’s most vulnerable groups.

About Me:

For those who don’t know me, I’m Rionne McAvoy, a documentary filmmaker, pro wrestler, and martial artist. I’ve been living in Japan for over 22 years, and my passion is telling stories that matter—stories that inspire change, that make people think, and, most importantly, that give a voice to those who need it most.

About the Film:

The Ones Left Behind: The Plight of Single Mothers in Japan is a documentary that reveals the hidden poverty facing single mothers in Japan, highlighting their struggles to provide for their children in a society that often leaves them behind. The film has already won several awards and is now gaining international attention.