The Silent Steps Of The Demon of Death - The Shinigami

The Terrifying Grim Reapers Of Japanese Lore

In Japan, there’s a belief that death doesn’t come by chance. It’s all arranged in a subtle, deliberate, and inevitable way by gods or demons of death called the shinigami. These “death gods” or “death spirits” serve as psychopomps (from the Greek word psychopompós) literally meaning the 'guide of souls,' from the mortal realm to their final destination.

死 Shi(ni) = death

神K(g)ami = god

These spiritual beings serve as guides between the mortal realm and the afterlife and the concept of shinigami has evolved significantly over time, gaining widespread recognition through manga, anime, and other forms of modern media. Popularized in anime and manga such as Death Note , Bleach, Naruto, and Soul Eater, while the shinigami are often compared to the Grim Reaper, they’re generally represented in Japanese folklore more as facilitators of the natural cycle of life rather than as a frightening figures dragging the unwilling to the underworld.

I’ve been thinking about life and death lately, and how both can feel so scripted. How a single decision, a single second, can alter the course of everything. We tell ourselves we have control, that we are the architects of our own lives, but sometimes we are left staring at the wreckage of a moment we never saw coming, realising only then that the signs were there all along.

When you lose someone close to you, you replay certain moments over and over in your mind, searching for the place where the shift happened. I think that at the end of the day, the unsettling truth is that we don’t always get to know. And that’s where the shinigami come in, working in the spaces between what we see and what we understand. By the time we recognize their presence, their work is already done.

How long have the shinigami been around?

As Ancient Origins (a wonderful website) explains, the shinigami didn’t appear in Japanese folklore until the 18th or 19th centuries, around the time that ideas from Western culture started mixing with traditional Buddhist, Taoist, and Shinto beliefs in Japan.

In fact, the word shinigami wasn’t used until the Edo period (1600 to 1868), with the first known instances being a number of 18th-century puppet plays (ningyo joruri), about men and women being compelled to their deaths by spirits of death.

While the shinigami are similar to the Grim Reaper, there are a few important differences between the two.

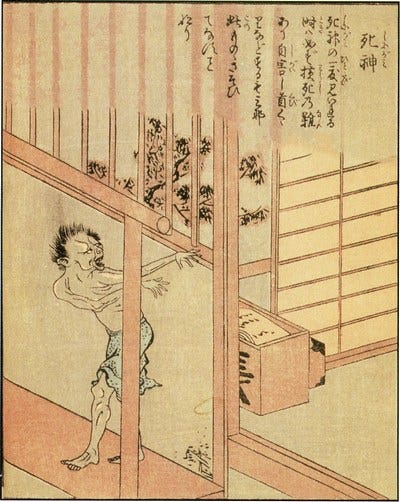

In the West, we see the Grim Reaper as this terrifying figure like the picture above, hooded, scythe in hand, the personification of death itself who simply collects souls. But in Japanese folklore, death isn’t about some lone figure hunting you down, it’s just part of the natural order of things. It depends on who you talk to and what you read, but it is said that the shinigami aren’t the all terrifying monsters like the Reaper, they are demons who are basically just doing their job, keeping the cycle of life and death in motion. But when you talk to people who have lost a loved one, they are indeed terrifying like the Grim Reaper. Confusion about who they are is a poetic reminder that death comes for everyone and its timing is never really ours to decide. It sux for those left behind who have to deal with the pain.

The shinigami are cruel, cold, and calculated. They don’t rush and they don’t act on impulse. We start asking questions, trying to make sense of the confusion.

Why didn’t I say something?

Why didn’t I do something more when I had the chance?

But the shinigami were waiting, planning and they set the pieces in motion so that when the moment arrives, everything falls into place with haunting precision and you know deep in your heart, the shinigami has come for you or for a loved one and the questions stop.

Some say they whisper to those whose time has come, gently guiding them toward the end. Others believe they manipulate the world itself with small and subtle changes that in reality seem insignificant at first but later reveal their meaning in hindsight, which is, as they say, always 20-20. A missed phone call prevents a final goodbye. A sudden, inexplicable feeling urges someone to turn left instead of right. Bad advice from a doctor who doesn’t care enough to do a check that could have saved someone’s life, or a sudden change of heart in something you wanted to do. They are moments that seem like nothing. Later, they seem like everything.

Can we see them?

The visibility of shinigami remains limited to specific circumstances and their appearances vary significantly, unlike the Western Grim Reaper’s consistent skeletal form.

Individuals approaching death can see them

People with spiritual awareness can see them

Those with supernatural connections can see them

The shinigami are also inconsistent in terms of how they’re physically described in different works. Sometimes, they are depicted as small and childlike, and other times as tall, skeletal women. Often, they are said to wear black kimonos and to have long white hair.

Japanese folk religion points to one story in particular to explain where the legends of the shinigami may have come from.

Who created the shinigami?

According to a legend from Shinto, the gods Izanami and Izanagi may have been the ones who created the shinigami (as well as the imperial family apparently!)

Izanami (“she who invites”) and her husband Izanagi (“he who invites”) are the first gods of the Shinto religion who are believed to have created the islands of Japan, breathed life into the first people, and are the ones who gave birth to many of the other Shinto gods. Izanami was the mother of creation who became the goddess of the underworld.

Published in the 8th-century book Kojiki by O No Yasumaro, an ancient text of Japanese mythology, the universe was initially a chaotic void and Izanagi and Izanami were tasked with creating the world.

I first heard this story way back in early 2002 when I was teaching English as a 21 year old at NOVA. The chain conversation school (eventually shut down due to scandals involving company funds) had a “free talk room” and a rather eccentric guy called Junichi (will never forget his name) told me about them.

Armed with their jeweled spear, legend has it that they made the island of Onogoro and its palace together. This was the starting point for the birth of the kami (gods) who were their children. Their initial try at having kids led to Hiruko, a leech child, who was born without bones and was abandoned by his parents and set adrift in a reed boat. He eventually became the god Ebisu, one of the seven gods of good luck, associated with good fortune and fishing. Not to be discouraged and after a chat with the elder gods, they went on to create the islands of Japan and those seven gods of good luck.

Everything went wrong when Izanami was badly injured and eventually died after giving birth to the fire god Kagutsuchi. In an act of grief and rage, her husband Izanagi killed Kagutsuchi with his 'ten-grasp sword' but was left alone in his grief.

He could not accept it and journeyed to yomi, the land of the dead, hoping to bring his wife back. Once there, Izanagi was overjoyed when he spotted his wife through the castle gates. He begged for her to come back with him but she told him that she can not leave the Underworld, as she has already tasted the food there.

Izanami tells her husband that she will ask the gods of the Underworld for permission to leave. As she walks into the castle, she makes Izanagi promise to remain outside the castle walls and not to look inside.

Izanagi waits as long as he can, but as night falls, he becomes impatient and breaks into the castle. But when he found her, she was no longer the goddess he had loved. Her body had rotted and her spirit chained to the Underworld. She was sleeping in a deathlike trance and Izanagi ran from the room in terror, leaving Izanami behind.

Enraged at both Izanagi’s rejection and his failure to keep his promise, Izanami chases after her husband who manages to escape, placing a boulder at the entrance to the Underworld, creating a divide between the land of the living and the dead.

According to legend, Izanami was so enraged at his betrayal that she promised to kill thousands of innocents as retribution. For this reason, many now see Izanami as the first shinigami.

These events have a big influence on the cleansing rituals in Shinto religion. Their story has left a deep imprint on Japanese culture, art, and religious practices, showing how significant their love story is and their part in the making of Japan and its gods.

I’ve been thinking about this story a lot lately. How death isn’t sudden or random, but something deeply woven into existence itself. In the end, Izanagi failed. He thought he had control, that he could bring back what was lost, but the truth had already been written. The moment he stepped into the underworld, the ending had been set.

That’s how it feels, sometimes. Like things are moving according to a plan we aren’t privy to and then suddenly, it all makes sense. The shinigami had been at work.

I wonder sometimes if they linger afterward, watching as we try to make sense of it all. Watching as we sift through memories, looking for meaning where there may be none. Do they pity us? Do they regret their role? Or do they simply move on, silent as ever, already setting the next pieces in place? I’d say the latter.

It’s a strange thing, realizing that something greater may be at play. That what we call coincidence may not be coincidence at all. That maybe, just maybe, everything happened exactly as it was meant to. And if that’s true then the only question left is: who set it in motion?

Rionne McAvoy is the director of the award-winning documentary The One's Left Behind: The Plight of Single Mothers in Japan, showcasing his dedication to addressing pressing social issues. A committed documentary filmmaker and professional wrestler, he explores critical themes with passion and insight. Additionally, he has a keen interest in post-World War II Japan, particularly the intricate connections between politicians and gangsters during that era. Known in the wrestling ring as Rionne Fujiwara, he brings the same determination and storytelling prowess from his wrestling persona to his filmmaking endeavors.

Love this mythopoetic weaving and wondering. A thoughtful and insightful piece that shares a Japanese cultural lens that spans both an ancient and modern take on the Japanese death demons.

another outstanding piece

A first rate writer as well as a first rate filmmaker!