Review of Netflix's "The Queen of Villains"

The fascinating world of women's professional wrestling in Showa-era Japan

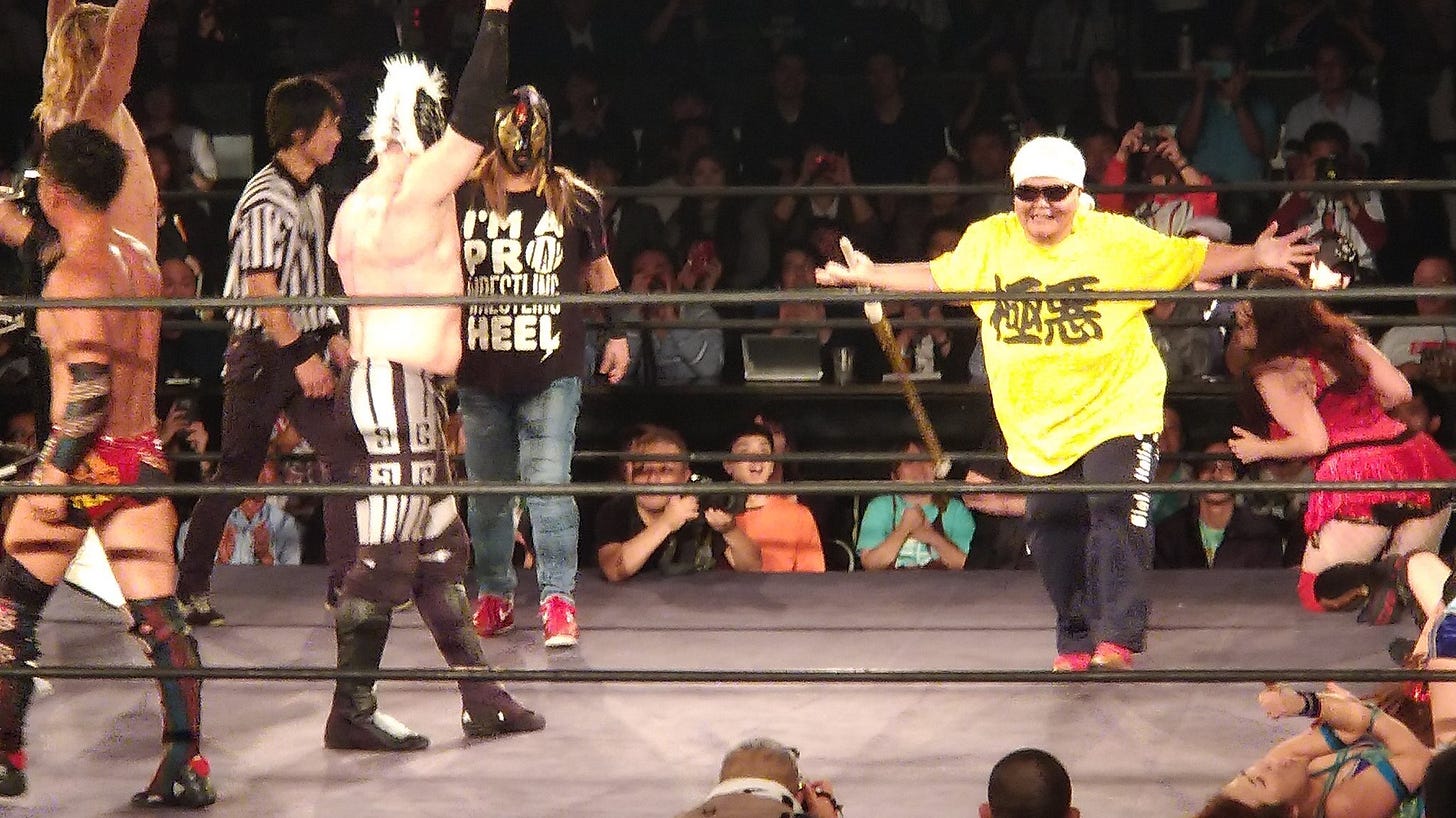

Before I start, I want to say that I may be a little bit biased and harsh, given my involvement in the inner workings of the professional wrestling industry in Japan for over 12 years. I have wrestled for Chigusa Nagayo's company and also have faced the legendary Dump Matsumoto in a match before. Dump was also on numerous shows that I wrestled on.

If you like these kinds of stories, you may like the road I took to becoming a professional wrestler in Japan. I started out with former WWE Superstar Tajiri before joining to The Great Muta’s group Wrestle-1 and also spent stints in AJPW and Pro Wrestling Noah to name a few.

Let’s start with Dump Matsumoto. She is a legendary Japanese professional wrestler, best known being the fearsome heel (villain) during the boom 1980s, an era affectionately known as Showa in Japan. The term Showa refers to the generation that lived during Japan's Showa era (named after Emperor Showa who lived from 1926–1989), a period marked by profound transformation, including the hardships of World War II, rapid post-war reconstruction, and the economic miracle of the 1960s. For many, it symbolizes resilience, hard work, and traditional values deeply rooted in perseverance and national pride. When you hear Showa in Japan, most people think of the 70’s and 80’s and when you say “Showa Pro Wrestling” it always refers to the boom period of the 70’s and 80’s when companies run by Antonio Inoki (New Japan Pro Wrestling) and Giant Baba (All Japan Pro wrestling) ruled the land and the airwaves.

I will say one thing and I’m going to get backlash. Women’s professional wrestling in Japan right now is not great. It’s time for a lot of the girls to go back to basics and learn how to do a legitimate lockup or learn proper shoot submission wrestling as it’s now simply a dance choreographed, idol dominated spectacle. Many of the girls go into it wanting to be wrestlers and the wrestling companies also produce soft core porn magazine books to take money off the fans. Make no mistake about it though, when Dump Matsumoto rose to prominence in All Japan Women's Pro-Wrestling (AJW), where she became notorious for her violent, brawler style and intimidating presence in the ring, Japanese women’s wrestling was at the top of it’s game, on-par with the top male wrestlers of the day. Dump Matsumoto, as well as Chigusa Nagayo (one half of the Crush Gals), Lioness Asuka (the other half of the Crush Gals), Jaguar Yokota, Devil Masami, Manami Toyota, Bull Nakano are just a few of the incredible female wrestlers to come from that period. Just check out this NBC America news report on women’s wrestling in 1986 and listen to the girls in the crowd scream!

Indeed a lot of the Showa women’s matches were far more brutal than their male counterpart’s matches. Dump’s signature look, complete with chains, kendo sticks, and a menacing scowl, made her one of the most feared figures in women's wrestling, one of the most unforgettable villains this country has ever seen.

Dump played a pivotal role in elevating the popularity of women’s wrestling during the 1980s and is remembered for her groundbreaking contributions to women's wrestling, both for her in-ring talent and for helping shape the narrative of powerful female heels in the sport.

As a professional wrestler and filmmaker myself, I was extremely curious going into Netflix’s The Queen of Villains. While the series nails the atmosphere and cultural feel of the period, from the gritty streets to the tension-filled arenas, as with most Japanese TV dramas and films, the acting leaves much to be desired. While the West (and Korea too) have evolved into the gritty, realistic acting that we take for granted today, Japanese TV and films are still stuck in the Casablanca time period. Don’t just take that from me, Beat Takashi said the same thing about comedy in Japan during an FCCJ press conference (around the 5:00 mark) last year. Japanese comedy hasn’t evolved, it’s stuck in the Laurel and Hardy and days. The same goes for TV and film and it’s why Korea is blowing Japan out of the water with their entertainment industry. Japan is so far behind it’s impossible to catch up.

As I am very familiar with many of the central figures portrayed, including both Chigusa Nagayo and Dump Matsumoto, I had high expectations for how the performers would embody the larger-than-life personas of these legends. Unfortunately, the actors often fail to capture the intensity, grit, and charisma required for these roles. The portrayal of Dump Matsumoto by comedian Yuriyan Retriever feels wrong. It lacks the menace and aura of dominance that made her a feared figure in the ring. While the show tries to compensate with dramatic moments, the emotional range of Yuriyan Retriever is so limited (again, she’s a slapstick comedian stuck in the Laurel and Hardy days) that she doesn’t channel any fierce, fearsome queen of the wrestling ring aura.

Where the show does excel is in recreating the Showa era. From the 80’s style cars and cigarette vending machines on the streets, to the understated but accurate details of wrestling culture in Showa Japan, The Queen of Villains brilliantly captures the essence of the time. It transports viewers back to an era of grueling matches, where the line between reality and performance blurred, and where a kendo stick to the head wasn’t just a prop but a genuine, painful part of the spectacle—I can personally attest to that, having been on the receiving end of one in a match against Dump Matsumoto. The show gets those visceral elements right, adding an authentic flavor for wrestling fans. It’s just let down by the awful acting - but probably the best that Japan can come up with right now.

What I loved most about the show was the opening sequence of episode 1, when the filmmakers did a fantastic job of recreating Beauty Pair. I guarantee you will not get this song out of your head for days.

The wrestling choreography in the show, though not as dynamic as real-life performances, does its best to simulate the action. The girls in the show are often seen not doing moves properly but it’s quickly covered up in editing. The average viewer would never notice. I notice because 1. I am a wrestler and 2. I am a film editor!

If you’re looking for an authentic visual portrayal of Showa-era Japan and its unique wrestling scene, The Queen of Villains succeeds. But for those of us familiar with the personalities and the intricacies of wrestling culture, the lackluster performances undermine the potential emotional depth and dramatic weight the story could have delivered. It’s a missed opportunity in an otherwise well-researched and visually immersive show.

Rionne McAvoy is the director of the award-winning documentary The One's Left Behind: The Plight of Single Mothers in Japan, showcasing his dedication to addressing pressing social issues. A committed documentary filmmaker and professional wrestler, he explores critical themes with passion and insight. Additionally, he has a keen interest in post-World War II Japan, particularly the intricate connections between politicians and gangsters during that era. Known in the wrestling ring as Rionne Fujiwara, he brings the same determination and storytelling prowess from his wrestling persona to his filmmaking endeavors.

I often hear that familiarity breeds contempt. You are too close personally to the subject of pro-wrestling, and that will influence your view. I understand, since I find myself feeling similar thoughts about war movies and military themes. Too close to the subject, so things seem too flawed.

For those who are not in the puroresu ring, this Netflix series is acceptable, entertaining content. The portrayal of Showa era Japan is missing a bit, but once again, I am too close to the subject. I lived through that era in Tokyo and remember it too well. The on-screen portrayal is superficial and misses the real feel of the era.

As for the acting, Japan is known for directors that encourage over-acting. Seems to come from a cultural bias towards stage productions, such as the exaggerated expressions and emotions of kyogen, kabuki, or taishu-engeki. For a Japanese audience, this kind of over-acting is expected. For a non-Japanese audience, it will look odd or even bad. YMMV.

BTW, I was there in the audience during the 80s and saw many of these matches live. The real Beauty Pair performance was a lot better than how Netflix showed it. If you had seen them live, you would know that Netflix did not do justice to their in-ring act. They may not be the best singers, but the atmosphere they produced was top notch for a wrestling fan crowd. At the same time, Netflix portrayed the Crush Gals in a very tame manner. Ayame Goriki was miscast as Lioness Asuka, for sure. Chigusa Nagayo having a hand in the Netflix production certainly had a strong effect in this regard.