Tatami: traditional Japanese mats made of woven straw, used as flooring in homes and martial arts dojos. More than just something you stand on, tatami carries the weight of culture, discipline, and memory. You might wonder after reading this, why all the posts about growing up? About being raised in Japan for half my life? This substack will one day be a book, so getting my thoughts out in words is important.

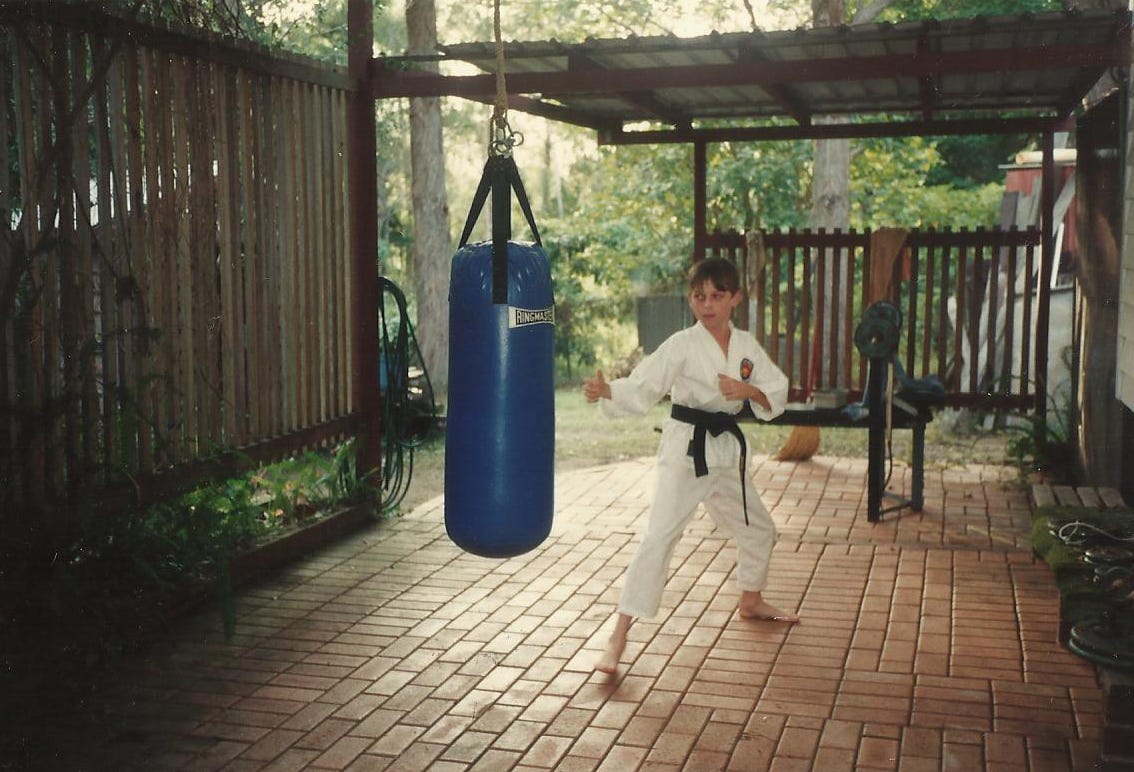

My earliest memories of training aren’t on a tatami inside a dojo or a gym though. They’re in the back courtyard, barefoot, sweating under a Queensland sun, the sound of a worn-out sandbag imprinting itself on my shin at my house in Australia. My dad, a short northern Englishman with a thick accent and possible ADHD that could’ve powered a freight train, had me kicking that sandbag for two hours every single day. Not after dinner, but as soon as I got home from school and before I was allowed to even touch a schoolbook. He used to randomly stand guard at the window above from inside the house to make sure I was not slacking off.

For the times, he wasn’t cruel with his training requirements. Today that kind of training might be considered borderline child abuse by some, but I never felt that way back then or even now. I think he just believed that discipline and hard work came before everything else.

When I got beaten up at the age of eight for being a little smart ass to an older boy, something clicked in him. I wonder if he saw a bit of himself in my humiliation? He had been raised in Workington, England (an old mining town that doesn’t have much going for it once the mines shut down decades ago) and was always taught by his dad to fight back no matter what. If he got a “hiding” at school, he wasn’t allowed back in the house until it was settled outside (or so he proudly used to say). Those were different times and he tried to instill that in me. Once when I was one of the last boys (aged nine at the time) to ever get the cane (twice on the same hand!) at primary school, my dad only ever asked me “did you cry in front of the headmaster?” and when I admitted I did, he gave me a lecture about showing weakness in front of people.

“Don’t EVER let authority beat you or see you as weak. You take that and smile.”

So he pushed me forward. Tae Kwon Do was the first stop. Not for fitness or self-esteem, but for toughness. No boy of his was ever going to get beaten up again. It was never in my heart to be a martial artist, but that’s what being pushed beyond what you think you can do is all about. I would learn this even more so in Japanese pro wrestling training, where puking after training was considered normal. The Japanese old school training methods are sadistic, just ask the baseball players! I had to learn from a young age that even if you don’t want to do something, sometimes it just had to be done (like my dad holding the kicking bag and insisting on 100 roundhouse kicks before bed). How on earth I was able to sleep beats me.

There is a moral to this story and I am not writing this to toot my own horn. Hear me out!

By the time I was thirteen, I had my second dan black belt and was training with the Australian junior or national team. It sounds impressive until you realise it was 1993 and Tae Kwon Do was gearing up for the Olympics. The Australians were recruiting and desperately needed their next generation of possible olympic stars. Our sessions were held on the old fields of the Brisbane Broncos rugby league team. The turf was uneven and the floodlights buzzed but it was nerve wracking. In fact, I still feel the same these days before a pro wrestling match.

At the junior gradings, I was one of only two black belts that the red belt third-stripes (the level before black) had to spar in order to earn their own black belt. It was like being the final boss in a video game, except I wasn’t there to help anyone pass. My dad used to beat thoughts into my little brain “You don’t give that little bastard anything. Kick the shit out of him.” I was thirteen and in full Terminator mode. Add in his English accent for more clarity if you want. If you grow up training that way, nonstop from childhood, it becomes more than habit, it becomes your language.

By then, fighting was already in my brain, but still not in my heart. I have my mother’s heart, she is a kind and honest woman who always wants to be a good person through her actions. She volunteers to sit with old people who are in the last stages of their lives, just to sit and talk and read the bible to them. So there has always been massive conflict between what my heart and brain wants, even today. Maybe that’s why I am pro wrestler and not an MMA fighter! I’ll take the non-confrontational way out if there’s a chance. Then again, MMA didn’t exist when I was a kid, so who knows.

So I am 14 and just when everything felt like Tae Kwon Do was moving toward something like a national future, a bigger stage, a shot at glory, my dad pulled the rug out from under me. He pulled me out of Tae Kwon Do altogether!

“You can kick like a stallion,” he said, not unproudly. “But you can’t punch your way out of a wet paper bag.”

I will never forget those exact words as long as I live. And that was that. I put my little Tae Kwon Do grading card in my desk drawer and never pulled it out again.

He enrolled me in karate. New gi. New sensei. New belt, from black to white. New ego to build from scratch. I was crushed and it felt like betrayal, but I had no choice.

I trained very hard for two years but one day I just quit. I was sixteen and wanted to play basketball and talk to girls. When I informed my dad of the decision to quit karate, he screamed profanities at me, stormed out of the room, and didn’t talk to me for a year.

“You f%cking little ungrateful brat, you’ve wasted all my time and money. F$ck off,” were the words I believe he used. I was crushed even more and unable to understand and process what was going on. He never apologised or thought about those words ever again. I remember sitting on my bed with my mother crying. She just held me and said “it’s ok, don’t worry.” Love you mum :)

Three years later, at nineteen, I was aimlessly scrolling through ICQ. For those who remember, ICQ was the internet’s chaotic first attempt at global conversation. Random beeps. Random people. It was the wild west before MSN Messenger and later what we now know as WhatsApp etc, that cleaned things up. I will never forget my username, 14141460. How could you, right?

By pure chance, I reconnected with a girl I’d had a schoolboy crush on from fourteen to sixteen. She was the daughter of my old karate sensei. She asked me to come back to the dojo. I had no intention of ever doing karate again. But she asked and I went. 63kg Rionne turned up in board shorts and thongs (what we Aussies call flip flops) and I sat through the class just waiting for the clock to hit 8pm so I could talk to Bianca. Her mother, sensei’s wife, then proceeded to sign me up and had me ordering a new uniform within half an hour of the class ending. It wasn’t a choice. It was destiny by ambush! 6 months later, after three years of no karate, I became Queensland state karate champion. And who slipped in and out without telling me he was going to be there? Yeah… my dad. Was I back in karate just to please him? Possibly. To try and date Bianca? Most definitely. Did either happen? No. You don’t always get the girl like in the movies, but the three trophies weren’t too bad.

Then came Japan.

I flew over to visit a mate who was studying here. I trained a little while I was in the country, but it wasn’t long before I discovered Roppongi. Back then, Roppongi wasn’t the sleek, cosmopolitan place it tries to be today. It was known as the devil’s playground. Neon signs, foreigners with wild eyes and girls with no place to go but the nightclubs that never closed. The streets never slept (mostly because the trains stopped at midnight and started again at 5am) and the people never stopped partying.

The music and booze were constant and swallowed everything, including any hope of consistent training. I lost the path again but the seed had actually already been planted.

My dad had started aikido when I was ten and used me as his uke (the person you do martial arts techniques on in training) whenever he had to prepare for a grading or a demonstration. Where did we train? Not in a dojo, but in our swimming pool! He’d be rehearsing techniques while I tried not to drown. It was fun, ridiculous and unforgettable. I didn’t realise it at the time, but those hours of being thrown in chlorinated water in the belting sun would eventually shape my future more than I could know.

At twenty-one, I came back to Japan full time and started working as an English teacher for Nova. Nova was the McDonald’s of English conversation schools. Mass-produced, outside every train station, with products as healthy as a Big Mac (literally any man and his dog could be a Nova teacher). Nova’s president eventually was arrested for fraud and embezzlement and after his arrest the police found a sex dungeon hidden in the Nova Towers. The job paid the bills and gave me a visa so I was happy, but something was missing.

The tatami. The mats of the dojo.

I missed it more than I expected. It was the texture of my youth so I joined the Aikikai Hombu Dojo.

I didn’t speak Japanese. I thought I did. I walked into the dojo for my first class, tried to say, “This is my first class,” and accidentally told the teacher, “You are the best.” The teacher smiled awkwardly.

Eventually, I went back to Australia to finish my university degree in Japanese language and joined my dad’s aikido dojo. That was when everything started coming together. I wasn’t doing martial arts to prove anything anymore. I was doing it to understand something. I came back to Japan in December of 2005 and have never left.

Around 2007, though, something started to itch at the back of my mind. I missed real combat. The fight or flight, the chaos of competition and especially the kicks. Aikido, for all its beauty and precision, didn’t offer that. So I joined Ihara Kickboxing Gym and set my sights on becoming a professional kickboxer, making it all the way to my first “pro test” before getting knocked out cold. I knew then and there it wasn’t for me. I would make this choice in film later on too.

The truth is, I had always wanted to be a professional wrestler since around that time I got the cane at school in 1989. My late friend Eric once told me something that stuck.

“In Japan, pro wrestlers go to MMA (not very successfully). MMA guys go to pro wrestling. Kickboxers go to MMA. It’s all mixed up. You never know what is going to lead where. Just join the kickboxing gym.”

So I did. That decision took me to places I never imagined, and you can read about that here:

In reality I had only gotten my foot in the pro wrestling door because of the kickboxing. But even before that, I had tried to become a movie action star. I had the kicks and the dream but what I didn’t have was any acting talent. I sucked. There’s a YouTube link below to prove it. Who else would take a fake gun onto a massive big ship docked at a Tokyo port, with no permission to shoot (film, not the gun)? The result is hilarious and all in the YouTube clip below.

The American director behind that project was one of my aikido students and friends at the time. He quit after the first day of filming for vague reasons I still don’t understand today, but it was fate. I had no interest in directing! I wanted to be the lead. Instead, I found myself running the show.

I should have seen it coming. When I was twelve, my dad handed me a video camera and told me to film his aikido classes and gradings. I had been a cameraman long before I was ever a fighter or a storyteller, I just hadn’t realised it yet. That moment, that gift of a camera, was more than a nudge. It was the starting point of a path I was always meant to walk and in the end, I realised that I am nothing without either! I need martial arts and training, and I need my camera, and who can I really thank for all that? My dad. He wasn’t always nice but you know the saying about life and lemons. At 43 years old, I am making lemonade professionally in two completely different fields.

Now I make documentaries about real fighters: single parents, children who are contemplating taking their own lives, about people on the edge, about The Ones Left Behind. I still wrestle part time and I want to make sure that everyone knows, I do not think I am special in any way because the tatami will always remind you that you are not. There will always be someone on it to remind you of that pretty quickly. I was just raised to go all in. Less social media and tablets and more kids in martial arts would be great. Hell, more adults would be too. We humans need to belong to a community (whether that be martial arts or something completely different), and we do need some discipline. My Canadian aikido friends smash each other on the tatami, and then smash down beers and smash a roasted pig during their summer camps. Camaraderie at its best.

So I guess what I am trying to say is this. Whether it was kicking a sandbag until my legs got sore, or getting thrown in the swimming pool for the fiftieth time, filming hours of footage no one else would watch, or painfully subtitling in English every single word of every Japanese interview I shot just to know that I hadn’t missed anything, I try to give it everything I have.

If there is anything I have learned, it is that life does not need to be one straight path. It can twist and loop and collapse on itself. You can chase as many goals as you want. What matters is how much of yourself you are willing to give. If you give one hundred and ten percent, if you show up, if you grind, eventually you will find the path that was meant to be yours.

And sometimes, you may realise it was there all along.

Thanks, Dad, for being the one who drilled the work into me. Whether it was kicking the sandbag until my legs gave out or filming your aikido gradings when I could barely hold the camera steady (instead of being at a friend’s birthday party). And thank you, Mum, for showing me what it means to try to be a good person. We can only do our best, as you always used to say.

Or, as Dad liked to put it when I asked for a break:

“Break? You can have a break when you're asleep tonight. Now kick it again.”

Cheers to both of you.

![平成の記憶:写真で振り返る「平成」 [写真特集3/25] | 毎日新聞 平成の記憶:写真で振り返る「平成」 [写真特集3/25] | 毎日新聞](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!k15A!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd73c8d23-a981-46e6-abcb-9c1e6754e92a_800x548.jpeg)